Webinar: Archaeological and Interpretive Research at St. Clair’s Defeat and the Battle of Fort Recovery

Wednesday, December 13, 1:00 pm

We have a historical archaeology focus for December as we welcome Christine Thompson of Ball State University to discuss frontier Ohio in the 1790s. The Northwest Indian War battles St. Clair’s Defeat (1791) and Battle of Fort Recovery (1794) involved multiple Native Tribes and the U.S. military. Over 12 years of archaeological, preservation, and interpretive research at the battlefield has evolved into updated interpretation co-created with descendent Tribes. Chris will share a summary of this work, the funding awarded for these projects, and focus on two major interpretive products including an online walking tour/wayside exhibits, and a traveling exhibit St. Clair’s Defeat: A New View of the Conflict.

About our presenter:

Bio: Christine Thompson is the Assistant Director and Archaeologist at the Applied Anthropology Laboratories (AAL), Ball State University. Her research interests include the Late Archaic Glacial Kame culture, public archaeology, NAGPRA, and interpretation of historic battlefields. She works to fulfill the AAL mission of inspiring and preparing AAL student employees for the workforce by providing students hands-on learning opportunities through the fulfillment of grant awards and cultural resource management contracts. Thompson strives to build lasting partnerships with Federally Recognized Tribes, communities, museums, historical societies, and other groups while collaborating on funded research projects.

Tales From a Privy Shaft Part 2

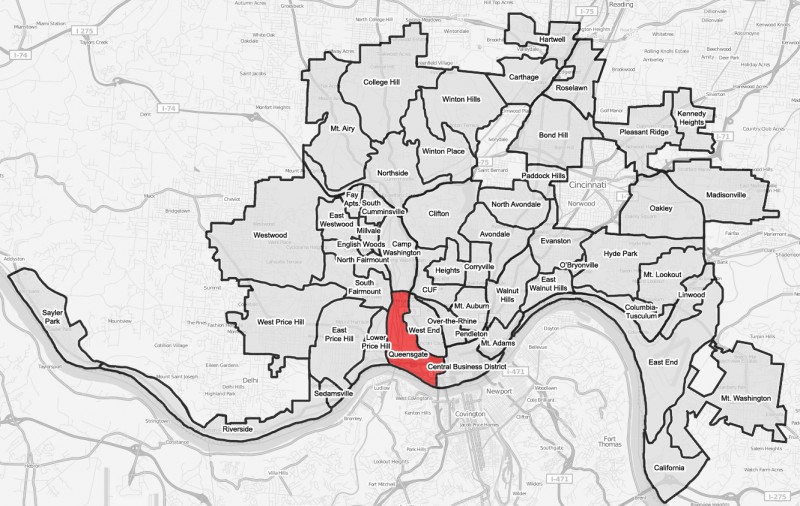

This blog post is part 2 of 3 telling the story of urban archaeology in a Cincinnati neighborhood. All information is credited to the archaeology report, “Queensgate II: An Archaeological View of Nineteenth Century Cincinnati,” by Thomas Cinadr and Robert Genheimer. The first part of this story left off discussing the process Cinadr and Genheimer used in selecting the lots. Especially when it comes to urban archaeology, it is important to remember site activity occurred not only in the house, but the entire lot. While today we throw meal leftovers and unneeded parts down the disposal or in the garbage can, get our water from the pipes in our house, and use the toilet in the bathroom, prior to the 20th century these were outdoor activities. Excavations to expose these activities and the differences between classes were the main objectives of this investigation. This blog will focus on the history of each lot and the excavation of each feature by Miami Purchase Association. The history of each lot was provided by Stephen Gordon and Elisabeth Tuttle’s 1981 study, “Queensgate II: A Preliminary Historical Site Report.”

Betts Longworth Historic District (formerly Queensgate II) taken July, 1982.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, OHIO,31-CINT,20-2

425 Chestnut Street

Cyrus Dempsey purchased this lot in 1847, and a house was built by 1849. Cyrus’ wife, Sarah, was a schoolteacher, and following Cyrus’ death Sarah remarried and remained in this house. Her new husband worked his way up from a copyist to a bookkeeper. In 1868, a new middle-class family moved in here and remained until 1900. After this family, a German immigrant family moved into the house and remained there until 1941. Three families called this place home in the span of just over 90 years. After 1941, we see a change towards the working class and a noticeable transient type of tenant; 6 tenants in 26 years. The house stood vacant from 1969 until 1981, and was demolished the following year.

Archaeologists from Miami Purchase Association used a heavy duty pry bar was used to lift the massive concrete slab covering the privy shaft. A layer of 20th century debris was cleared and a brick pad was found. Beneath that was the circular limestone outline of the privy shaft. Much of the upper portions of the privy shaft contained ash and heat altered materials, butchered bone, and 20th century bottles and ceramics. After about 10 feet, there is a change from solely kitchen dumping material to the introduction of a loose brown seed filled matrix (decayed fecal material) intermixed with the kitchen refuse. According to Cinadr and Genheimer, the artifacts suggest that the deposit dates between the 1880s to early 20th century.

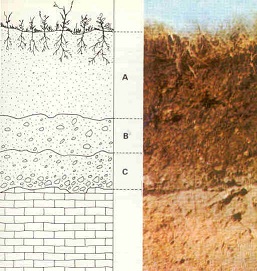

A new level was formed every 12 inches. A new horizon is formed as the soil changed. Credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Estructura-suelo.jpg#filelinks

Cinadr and Genheimer explain heavier amounts of 19th century glass and ceramics were uncovered in the next level below. Moving through the following three feet, there was still good evidence for kitchen refuse activity in addition to badly corroded metal and some glacial soils. The next horizon (layer of activity change) is confined to Level 14 and has heavy amounts of fecal material as well as architectural materials and kitchen refuse. Towards the end of this level, a gray clay matrix, followed by sand was found, indicating the Wisconsin Outwash and the bottom of the feature. Unlike the other privies studied by Cinadr and Genheimer, the diameter of this perimeter started at 3’8” and decreased with depth, ending at 2’3” at the base.

427 Chestnut Street

Next door stands a three story brick building. Archival research by Gordon and Tuttle (1981) shows that a frame house built sometime between 1848 and 1850 was standing in 1855. The current brick house replaced the frame structure by 1858. James Porter (a house painter) and his wife are first listed at this address in the 1849 city directory. A servant was listed in the 1880 census, but only for that year. James Porter passed away in 1889, and their grandson, E. A. Ferguson (16 years old) moved in with James’ wife, Margaret. He became a clerk and later a traveling salesman for a book company. In 1898, Margaret passed away and a man named Charles Dustin, listed as a night watchman, moved in. The mystery of Charles will play out later, but he is an example of unexpected mysteries uncovered during archaeology. The occupants of the house are unknown from 1901-1909. The next occupants listed began a line of working-class and African American tenants. While some stayed longer than others, there was significant movement in and out of the house by single males, mostly listed as laborers, which could suggest that people went where there was work. By 1981, the house was vacant.

A 13.5’ by 16’ addition once stood at the rear of the house, and is now covered by a concrete pad. Archaeologists removed the pad and found a dinner fork inscribed, “Extra Coin Silver Plate 1902.” Further testing revealed a laid brick pad, underneath which was a circular brick privy. Two large concrete slabs were found at the center of the shaft, indicating it was capped. Below that, excavations began. The way this privy shaft was used can be seen in the depositional patterns. Cinadr and Genheimer highlight three main activities which this privy was used for: dumping place for construction activities, kitchen refuse dumping, and as a toilet facility. The upper levels had horizons of solely kitchen dumping, as marked by butchered bone, shells, and ash from cooking byproduct. They point out the point in the depositional history where it is likely that indoor plumbing was installed. Below that point, kitchen dumping and fecal material are intermixed. The heavier the density of artifacts and the larger the horizon, the longer the privy was used for that function. The other activity found in the depositional history is construction. Using diagnostic artifacts including nails, coins, and bottles, dates can be narrowed for depositional activity.

The cistern, however, presented quite a different story for Miami Purchase Association. Beneath a large, thin concrete pad was an intact brick patio. Soon after beginning excavations, it became clear that this feature was a brick lined beehive cistern. Cinadr nad Genheimer explain that while it wasn’t surprising to find a cistern close to the house, it was somewhat surprising to find two walls extending from it to the north and the west. The wall extended from approximately three feet south to the eastern part of the cistern. After further excavations, it was determined that these walls belonged to the former addition. Due to the massive volume of soil and artifacts uncovered from within the cistern, a sampling method was enacted. Every fifth bucket of soil was screened for the first level, and every 10th bucket was screened after that. Hand trowling insured that whole bottles, bottle bases and tops, large bones, and larger artifacts were collected, while avoiding the substantial amounts of broken glass, and badly corroded metal. The next horizon was full of white ash with few artifacts. After the 4th level was reached, the walls no longer remained stable due to increasing dampness. Based on the dimensions, it was calculated that 3,180 gallons of water could be stored in this cistern.

In order to refine a construction date for the house, a builder’s trench was excavated below the front porch of the structure. Two feet below the surface, two large cut limestone slabs sitting parallel to each other were found. Below them, an intentionally laid brick area forming an arc was exposed. One possibility presented by Cinadr and Genheimer was the possibility that the limestone slabs were originally stairs, and once they became unstable, a wooden porch was constructed. Excavations point to two distinct periods of construction. It appears that Levels 1-4 (the upper 4 feet of the excavation) were considerably disturbed after construction of the house. The second period of construction was that of the house itself. Based on the artifacts identified, the dumping activity was unspecialized. Artifacts included a mix of kitchen refuse, marbles, buttons, a few coins, bottle glass, several ceramics of varying types, and architectural material, all dating to the mid-19th century.

416 Clark Street

This property, more commonly known as the William Betts House, was the beginnings of Queensgate. The brick house was built in 1804, with a brick and frame additions created at separate times but are known to pre-date the neighboring 1878 house, and a metal addition constructed in the 20th century. An early kitchen addition was badly damaged in the 1811 New Madrid Earthquake. The Betts family lived in the house until 1825, with 100 acres of the 111 acre property being split up and going to auction in 1833. It is thought that the privy currently on the property was constructed at this time. The 11 acres which were not sold included the 1804 house, which continued to be lived in by the Betts family until 1849. Dr. Alex Johnston and his family lived in the house during the 1850s and into the 1860s. The house remained part of the mercantile society until the turn of the century, when the occupants would more likely be considered middle class. Unlike the other two houses, the occupants were families who remained in the house for much longer periods. The house was occupied until 1981, when it stood vacant.

Clearing of a feature identified during the survey work revealed a large rectangular limestone lined walled feature which went right up to the foundation of the neighboring property. The privy fill was clearly disturbed for the first four feet. This all became known as Level 1. The privy shaft took a circular shape 4.2 feet in diameter by the next level. Artifact densities are light until the end of Level 3. After this, a large deposit of kitchen refuse (over 300 butchered bones), a variety of bottles, clay pipes, and medicine bottles including a Paine’s Celery Compound bottle were found. Based on diagnostic artifacts, this deposit dates roughly around the turn of the 20th century. A brick stabilization wall divided the privy shaft in half from Levels 4-7, with a portion of a wood beam at the bottom. Ash deposits surrounding the wall and arch fall continue through Level 13. Moderate densities of artifacts including flower pots, lamp glass, rubber combs, flavoring extract bottles, metal, electrical wire, window glass, sewing machine oil, tin cans, celluloid, leather shoes, clay pipes, and a variety of ceramics, medicinal bottles, and butchered bone were found within the ash deposits. Temporally sensitive artifacts place this portion of the privy at mid 1890s. As the excavation progressed, it was noted that fragments from a single artifacts were found in several levels. For example, fragments from a badly shattered brown spongeware teapot were found in Levels 6, but also in Level 14 (8 feet further below). Excavations ceased at after Level 19 due to decreasing stability of the walls and cold temperatures. The southern half of the privy shaft was excavated (unscreened) to 24’6” and then a 5 foot soil core was used to determined if any changes in soil would occur. The same types of artifacts were encountered until the bottom 2” of soil, which contained a dark seed-bearing level (likely fecal matter). Cinadr and Genheimer note that it appears this privy was quickly filled around the turn of the 19th century. The privy shaft was likely not capped until after 1959, as mid-20th century artifacts including a 1959 dog tag were found in the upper levels.

An attempt to locate depositions related to the construction of the house was made with a 3’x6’ unit next to a wall of the original portion of the house. A small assemblage of a mix of 19th and 20th century artifacts were located in the first level, including portions of a Diet 7-up bottle near mid 19th century ceramic shards. The next level below included architectural artifacts, as well fragments from an aqua glass bottle embossed Dr. D. Jayne’s Oleaginous Hair Tonic, whose business began in 1839. A thin gray clay material was noted near the foundation of the house from Level 1 until Level 4, extending out from the house up to 13” and then retreating back to the 3” from the foundation in Level 4. A variety of construction material, early 19th century ceramics, and a fragment of prehistoric chert, along with a small chert projectile point were found in the horizon next to the clay material. The foundation was made of undressed limestone slabs, which stops short of extending to the basement floor. Based on the artifacts uncovered, Cinadr and Genheimer explain that it is likely that this building trench dates to the construction of the original house and was undisturbed after the first level.

The last portion of this story will focus on the analysis of the artifacts and the results from Cinadr and Genheimer’s excavation. Today the William Betts house, at 416 Clark Street, is open as a museum. Learn more about the Betts family history and their house check out The Betts House.

Tales From a Privy Shaft part 1

Passing through downtown neighborhoods, many of us will notice the historic houses. Some are still as beautiful as the day they were completed and some are diamonds in the rough. Even driving through the dilapidated areas, I’m sure many of us wonder what the neighborhoods looked like in their prime. While the buildings are beautiful, I have always been attracted to the story behind the building. The story of who lived there, what the children played with, the health concerns of the former tenants, consumerism patterns and the story of the built past can be told through archaeology. Archaeology also can present new, untold stories, as we will see play out in the excavation of one of the privy shafts in the Queensgate II excavation. Since this project has so much detail and so many stories, it was necessary to split it into 3 blog posts.

How the Project Began

The Queensgate II neighborhood of the 19th century was substantially different than the Queensgate II of the late 20th century. The once thriving, diverse, highly populated area, had become a memory. With urban housing projects to the north, a booming business district to the east, and a freeway to the south and west, it is no surprise that by 1968, the population of this area was a mere 1280. The Queensgate II archaeology project was born from Ted Sunderhaus’ observation that despite excessive amounts of “excavations” by looters, and the vast amount of vacant buildings, there were still several areas which could provide the archaeological features necessary for the study of this diverse 19th century neighborhood. The Miami Purchase Association (now known as the Cincinnati Preservation Association) approached the City of Cincinnati with a plan to incorporate the results from an urban archaeological study into the mitigating factors of nearby redevelopment plans. The project was restricted to properties owned by the City of Cincinnati, within a five block area. The year prior, a detailed lot-by-lot history, which shed light on the class diversity, was conducted by Stephen Gordon and Elisabeth Tuttle. The archaeological research would provide additional insight on this topic.

Neighborhood Beginnings

The area known as Queensgate II (now known as the Betts Longworth District) is a 7-block, 117 acre area of Cincinnati bounded by Ezzard Charles Dr., Race Street, 6th Street, and I-75. Streets began being laid out as early as 1815 and a building boom followed the next decade. The city’s population tripled during the 1840s, and a change from frame construction to brick construction followed. Most people in the Queensgate II neighborhood were from New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, and were generally prosperous merchants. By 1870, however, a large German influx moved in and the original inhabitants moved away. Tensions between the Jewish population and non-Jewish population were common. In 1918, 55% of Cincinnati’s Jewish population lived in the West End (an area which includes Queensgate II). By 1930, however, only 5% remained. Also noteworthy was the increase in the black population. The 1860 census only listed 80 black people in the Seventh Ward, but by the 1920s, as much as 80% of Cincinnati’s black population lived in the West End. Demolition of Lincoln Park for Union Terminal in the 1930s, construction of the Interstate, and government housing drastically altered the streetscape.

Lot Selection

Since Queensgate II provided such a heterogeneous population, it was an ideal setting for the study. Preliminary surveys included looking through the back dirt left behind by looters, which were found to have a representative cross section of the past inhabitants with a wide array of artifacts recovered. Between the data provided from the Gordon and Tuttle report and a reconnaissance survey to identify potential features, along with factoring in economic diversity, potential for an intact feature, and the completeness of the historical record, selections for sites to be excavated was made.

A brick-lined privy shaft being sampled in Manhattan. Credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Bricklined_privy.jpg

Two lots were chosen, based on the selection criteria. The first held an 1840s frame structure and held an intact privy and cistern. Thorough documented history, including city directories which listed occupation for each resident, for this lot and the neighboring were found. The second location selected was the William Betts house. Similarly, a thorough history, intact privy and cistern were found on the lot. Additionally, it was decided that at least one builder’s trench be excavated to provide additional information.

I dig history, do you?

When I started college, I initially went to school for historic preservation. I always wondered what it was like to live a century ago, loved looking at historic photographs and hearing stories from the older residents in my town. While in college, on a whim, I took two archaeology classes one semester and fell in love. Yes, history provides you with names and dates and beautiful stories; however archaeology appealed to me because it is void of any opinion when it comes to telling the story of the past. I could tell you that I eat yogurt and snack bars at work, and drink a lot of water. However, if you took a peak at my garbage can next to my desk, you would see many candy and cereal bar wrappers, a few yogurt containers, and a lot of tea bags. Does that mean I live solely on those foods? No, however, it does mean that when I’m at that location, that is what I tend to consume. Material culture (physical remains, artifacts) can tell us a lot about history, particularly the history which doesn’t have a written record. It can also confirm written record.

If you think about a historic site as a whole with a story to tell, the standing structures tell just part of the story. A house, for example, can tell a lot about both the people who built the structure, as well as the current function. However, the house has not been there since time began. The landscape and what is beneath the land also has a rich history. Perhaps the area was formerly a farm. You might find footprints of former buildings, construction materials, farming tools, or animal bones. If there was a building and it collapsed in on itself, it will look different than if it was taken apart piece by piece. The material that the building was constructed of will leave different evidence and could show a different history. It could also show a chronology on the site, and help with dating the site. Materials such as nails were manufactured in different ways during certain set dates. Local resources used for construction material can also help provide the earliest date. Perhaps limestone or granite was quarried and used for building foundations, but you know that that ceased in a certain year. That year can be used as a point of reference.

One of the most important data components in archaeology is where the artifacts were found relative to the surface and relative to other physical or material culture. As archaeologists slowly excavate, the story of the history of that 1-meter square comes to light. Perhaps you find a 1980 penny and some plastic toys on the top surface, and then the next layer below you find the remnants of a glass bottle you can assign a date to, and kitchen utensils and maybe a broken dish, and then a layer of charcoal and burned wood when you know there was a house fire on that site at a certain date. This would indicate an area of undisturbed soil. However, many times all of those artifacts are lying next to each other; the 1980 penny sitting right next to a wire nail from the 1890s. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it still provides us with a picture of site activity because it would indicate that at some point the ground was disturbed. Perhaps it because it became plowed field, perhaps a tornado ripped through, or maybe a road came through nearby and the soil was dumped there.

In the next year, I will be writing blogs about different archaeology projects that have occurred or are occurring in Ohio. I encourage you to think about what other history is below ground, or what questions could be answered/confirmed through archaeology.