Dollars and Sense of Building Rehabilitation Findlay Ohio August 8, 2014

Heritage Ohio will bring their popular Building Rehabilitation Workshop to Findlay, Ohio August 8th. Historic commercial centers are seeing a strong resurgence in economic activity, as walk-able communities and urban living become more prevalent. This workshop is a good opportunity for building owners to learn more about successful financial strategies and how tools such as historic tax credits are used to renovate historic commercial structures. To view the agenda and register click HERE.

What do you geek out over?

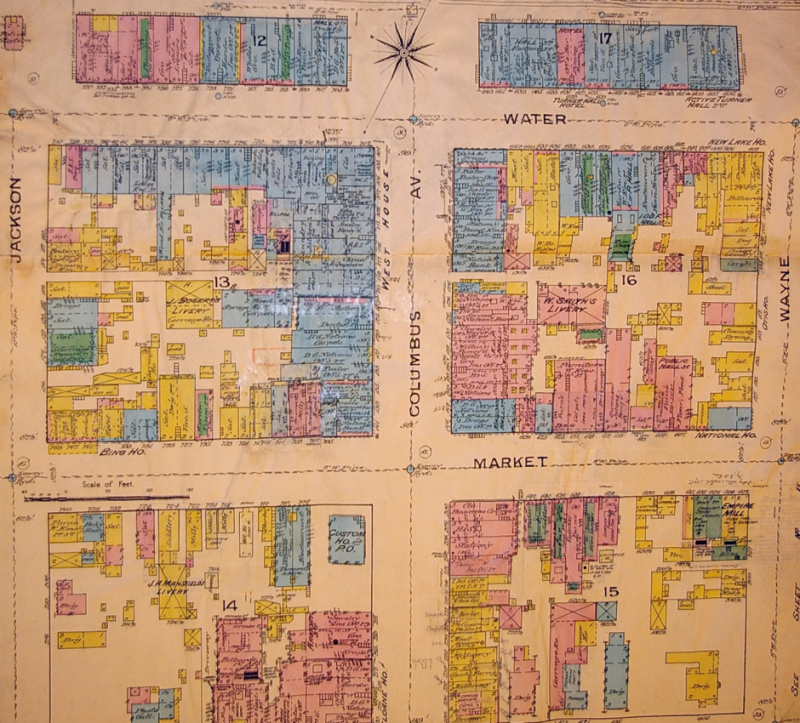

We all have something we geek out over, something we could spend hours looking at or studying. Maybe for you it is house colors, baseball statistics, the next way you might design your garden. For me, I regularly have what I call nerd nights where I pick a city and look at the Sanborn Fire Insurance maps. Sanborn maps are probably my favorite historic resource to consult and for this blog post, I am going to share why I get so excited when I find Sanborn maps.

Sanborn maps were created as a risk analysis tool for insurance underwriters. The maps were produced from 1866 through 1970. Population growth, demographic shifts, and urban sprawl all necessitated the need for regularly updated maps. A new map was created approximately every 10 years. The maps were created for towns and cities, but are generally not available for country properties. For the bigger cities, like Columbus or Cleveland, multiple volumes were needed to show the entire city. New York City reportedly has 39 volumes.

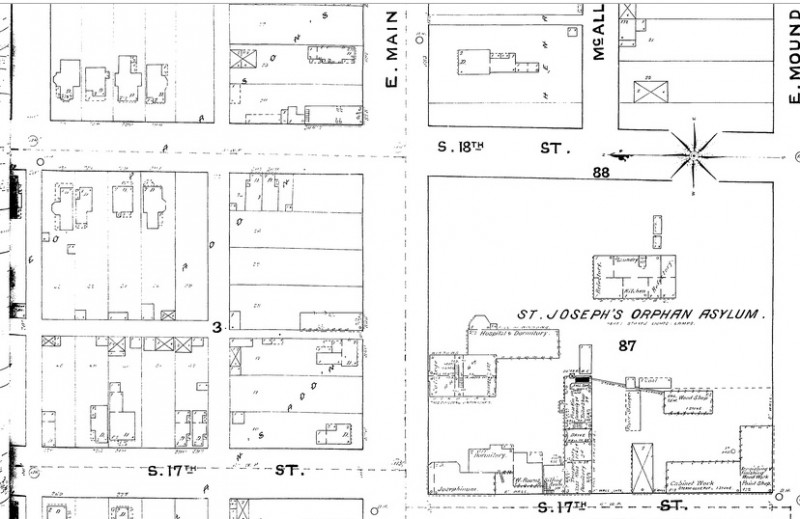

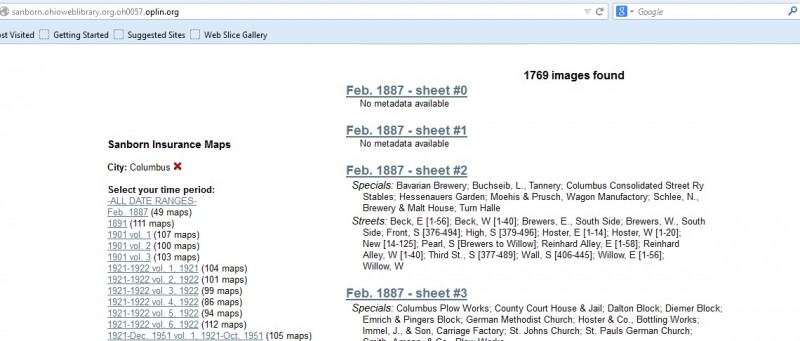

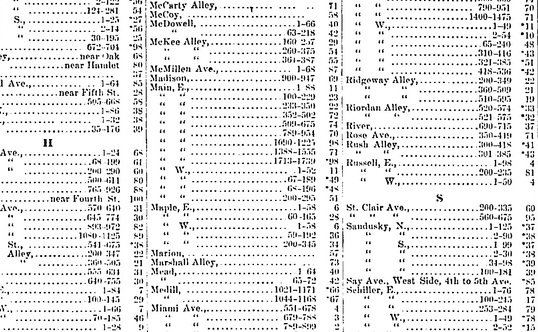

What’s so special about these maps? The wealth of detail and information which can be gained about a building for which there are no photographs can often be found in these maps. Each map was created on a piece of paper measuring 21” x 25” and was drawn at a scale of 50 feet to 1 inch. Everything was measured by tapeline, including the buildings, streets, sidewalks, and other utility features like distance to fire hydrants, gas lines, and water lines. The last part was particularly important for the fire insurance aspect of the maps. While the maps were created across the country, all maps are set up the same; all keyed the same, and demonstrate the same level of detail. Each volume was set up in the following order: a decorative title page, index of streets and “specials” which included schools, churches, and bigger businesses, a master key for the map (a map of the entire city color coded and numbered showing which map you would need to look up for your particular address), and some general information on population, geography, geology, economy, etc. In the case where multiple volumes were needed for a city, the master map would also let you know the volume number you needed if the area was adjoining the map you were currently using. Many states, including Ohio, have indexed digitized copies of the maps. If you have a library card, you can access this database (yes, even from your home in your comfy clothes). Here’s the link http://sanborn.ohioweblibrary.org.oh0057.oplin.org/ unfortunately, most of the digitized maps are black and white, but a lot of information can still be gained.

For this example, we will look at Heritage Ohio’s location. If you’ve never been to our office, feel free to do a quick Google maps street view search so you can get a 2014 idea of what the neighborhood looks like today. Our address is 846 East Main Street, Columbus. Click on the sanborn.ohioweblibrary link from above and type in Columbus on the search box. Now we have a list of the maps which have been digitized for the city. Notice that the first two years only have a single volume, then in 1901 there are 3 volumes, 1921 there are 6, and then in 1951 there are 9 volumes.

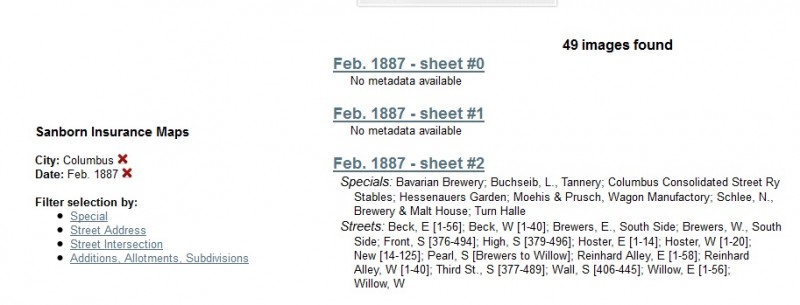

Go ahead and click on 1887. This will bring up a hyperlink for each map and also lists the “specials” and the streets (including the street numbers represented on that map). We want the street titled, Main, E which includes 846.

One of the first pages (usually page 0a or something similar) will always be the index, which if there were multiple volumes for the map would let us know if we were in the correct volume. In this case, the index is the first link. Clicking on the link, we find that there was a gap in the mapping between 824 and 893 East Main Street. Rather irksome knowing they cut off right where you need the map! So, click the red ‘x’ next to the Date: Feb, 1887 on the left side of the screen and it will bring you back to the list of maps.

Let’s try 1891. The index tells us that we need sheet number 70. On the right side of the screen, you can “jump to” a specific page. Go ahead and type in 70 and check it out. You should be able to zoom in to read the tiny details. If you had a chance to drive by our office or street viewed the neighborhood, you would know there is a square block of nothingness across the street from us. However, now you know what used to be there….an orphan asylum, and a large campus at that! The next map available is from 1901. I’ll save you the time and let you know you that our address is in Volume 3, sheet 320. Compared to the last map, we can see there has been a lot of development on our block. Our building is at the bottom of the sheet, where 844 and 848 are labeled. Yes, the one with the attached bowling alley. Focusing on this parcel of land, this map shows us that the building was 2 stories, with an opening to get between 844 and 848 in the middle, as well as access to the bowling alley. Keep going and find out what else became of the block. What became of the orphan asylum?

The color coded maps, in my opinion, are well worth the trip to the library or historical society. Here are the links for the keys so you can decipher the map. For the black and white maps, like the digitized maps mentioned in this blog, use this key: http://sanborn.umi.com/HelpFiles/bwkey.pdf

Here is a color coded key: http://www.loc.gov/rr/geogmap/sanborn/images/sankey22c.jpg

Here is a link for the many of the abbreviations found on the maps: http://www.newberry.org/sites/default/files/researchguide-attachments/sanbornabbrv.pdf

Tales From a Privy Shaft Part 2

This blog post is part 2 of 3 telling the story of urban archaeology in a Cincinnati neighborhood. All information is credited to the archaeology report, “Queensgate II: An Archaeological View of Nineteenth Century Cincinnati,” by Thomas Cinadr and Robert Genheimer. The first part of this story left off discussing the process Cinadr and Genheimer used in selecting the lots. Especially when it comes to urban archaeology, it is important to remember site activity occurred not only in the house, but the entire lot. While today we throw meal leftovers and unneeded parts down the disposal or in the garbage can, get our water from the pipes in our house, and use the toilet in the bathroom, prior to the 20th century these were outdoor activities. Excavations to expose these activities and the differences between classes were the main objectives of this investigation. This blog will focus on the history of each lot and the excavation of each feature by Miami Purchase Association. The history of each lot was provided by Stephen Gordon and Elisabeth Tuttle’s 1981 study, “Queensgate II: A Preliminary Historical Site Report.”

Betts Longworth Historic District (formerly Queensgate II) taken July, 1982.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, OHIO,31-CINT,20-2

425 Chestnut Street

Cyrus Dempsey purchased this lot in 1847, and a house was built by 1849. Cyrus’ wife, Sarah, was a schoolteacher, and following Cyrus’ death Sarah remarried and remained in this house. Her new husband worked his way up from a copyist to a bookkeeper. In 1868, a new middle-class family moved in here and remained until 1900. After this family, a German immigrant family moved into the house and remained there until 1941. Three families called this place home in the span of just over 90 years. After 1941, we see a change towards the working class and a noticeable transient type of tenant; 6 tenants in 26 years. The house stood vacant from 1969 until 1981, and was demolished the following year.

Archaeologists from Miami Purchase Association used a heavy duty pry bar was used to lift the massive concrete slab covering the privy shaft. A layer of 20th century debris was cleared and a brick pad was found. Beneath that was the circular limestone outline of the privy shaft. Much of the upper portions of the privy shaft contained ash and heat altered materials, butchered bone, and 20th century bottles and ceramics. After about 10 feet, there is a change from solely kitchen dumping material to the introduction of a loose brown seed filled matrix (decayed fecal material) intermixed with the kitchen refuse. According to Cinadr and Genheimer, the artifacts suggest that the deposit dates between the 1880s to early 20th century.

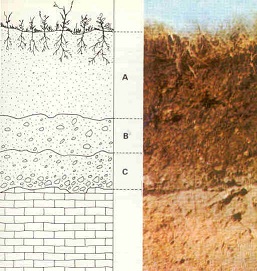

A new level was formed every 12 inches. A new horizon is formed as the soil changed. Credit: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Estructura-suelo.jpg#filelinks

Cinadr and Genheimer explain heavier amounts of 19th century glass and ceramics were uncovered in the next level below. Moving through the following three feet, there was still good evidence for kitchen refuse activity in addition to badly corroded metal and some glacial soils. The next horizon (layer of activity change) is confined to Level 14 and has heavy amounts of fecal material as well as architectural materials and kitchen refuse. Towards the end of this level, a gray clay matrix, followed by sand was found, indicating the Wisconsin Outwash and the bottom of the feature. Unlike the other privies studied by Cinadr and Genheimer, the diameter of this perimeter started at 3’8” and decreased with depth, ending at 2’3” at the base.

427 Chestnut Street

Next door stands a three story brick building. Archival research by Gordon and Tuttle (1981) shows that a frame house built sometime between 1848 and 1850 was standing in 1855. The current brick house replaced the frame structure by 1858. James Porter (a house painter) and his wife are first listed at this address in the 1849 city directory. A servant was listed in the 1880 census, but only for that year. James Porter passed away in 1889, and their grandson, E. A. Ferguson (16 years old) moved in with James’ wife, Margaret. He became a clerk and later a traveling salesman for a book company. In 1898, Margaret passed away and a man named Charles Dustin, listed as a night watchman, moved in. The mystery of Charles will play out later, but he is an example of unexpected mysteries uncovered during archaeology. The occupants of the house are unknown from 1901-1909. The next occupants listed began a line of working-class and African American tenants. While some stayed longer than others, there was significant movement in and out of the house by single males, mostly listed as laborers, which could suggest that people went where there was work. By 1981, the house was vacant.

A 13.5’ by 16’ addition once stood at the rear of the house, and is now covered by a concrete pad. Archaeologists removed the pad and found a dinner fork inscribed, “Extra Coin Silver Plate 1902.” Further testing revealed a laid brick pad, underneath which was a circular brick privy. Two large concrete slabs were found at the center of the shaft, indicating it was capped. Below that, excavations began. The way this privy shaft was used can be seen in the depositional patterns. Cinadr and Genheimer highlight three main activities which this privy was used for: dumping place for construction activities, kitchen refuse dumping, and as a toilet facility. The upper levels had horizons of solely kitchen dumping, as marked by butchered bone, shells, and ash from cooking byproduct. They point out the point in the depositional history where it is likely that indoor plumbing was installed. Below that point, kitchen dumping and fecal material are intermixed. The heavier the density of artifacts and the larger the horizon, the longer the privy was used for that function. The other activity found in the depositional history is construction. Using diagnostic artifacts including nails, coins, and bottles, dates can be narrowed for depositional activity.

The cistern, however, presented quite a different story for Miami Purchase Association. Beneath a large, thin concrete pad was an intact brick patio. Soon after beginning excavations, it became clear that this feature was a brick lined beehive cistern. Cinadr nad Genheimer explain that while it wasn’t surprising to find a cistern close to the house, it was somewhat surprising to find two walls extending from it to the north and the west. The wall extended from approximately three feet south to the eastern part of the cistern. After further excavations, it was determined that these walls belonged to the former addition. Due to the massive volume of soil and artifacts uncovered from within the cistern, a sampling method was enacted. Every fifth bucket of soil was screened for the first level, and every 10th bucket was screened after that. Hand trowling insured that whole bottles, bottle bases and tops, large bones, and larger artifacts were collected, while avoiding the substantial amounts of broken glass, and badly corroded metal. The next horizon was full of white ash with few artifacts. After the 4th level was reached, the walls no longer remained stable due to increasing dampness. Based on the dimensions, it was calculated that 3,180 gallons of water could be stored in this cistern.

In order to refine a construction date for the house, a builder’s trench was excavated below the front porch of the structure. Two feet below the surface, two large cut limestone slabs sitting parallel to each other were found. Below them, an intentionally laid brick area forming an arc was exposed. One possibility presented by Cinadr and Genheimer was the possibility that the limestone slabs were originally stairs, and once they became unstable, a wooden porch was constructed. Excavations point to two distinct periods of construction. It appears that Levels 1-4 (the upper 4 feet of the excavation) were considerably disturbed after construction of the house. The second period of construction was that of the house itself. Based on the artifacts identified, the dumping activity was unspecialized. Artifacts included a mix of kitchen refuse, marbles, buttons, a few coins, bottle glass, several ceramics of varying types, and architectural material, all dating to the mid-19th century.

416 Clark Street

This property, more commonly known as the William Betts House, was the beginnings of Queensgate. The brick house was built in 1804, with a brick and frame additions created at separate times but are known to pre-date the neighboring 1878 house, and a metal addition constructed in the 20th century. An early kitchen addition was badly damaged in the 1811 New Madrid Earthquake. The Betts family lived in the house until 1825, with 100 acres of the 111 acre property being split up and going to auction in 1833. It is thought that the privy currently on the property was constructed at this time. The 11 acres which were not sold included the 1804 house, which continued to be lived in by the Betts family until 1849. Dr. Alex Johnston and his family lived in the house during the 1850s and into the 1860s. The house remained part of the mercantile society until the turn of the century, when the occupants would more likely be considered middle class. Unlike the other two houses, the occupants were families who remained in the house for much longer periods. The house was occupied until 1981, when it stood vacant.

Clearing of a feature identified during the survey work revealed a large rectangular limestone lined walled feature which went right up to the foundation of the neighboring property. The privy fill was clearly disturbed for the first four feet. This all became known as Level 1. The privy shaft took a circular shape 4.2 feet in diameter by the next level. Artifact densities are light until the end of Level 3. After this, a large deposit of kitchen refuse (over 300 butchered bones), a variety of bottles, clay pipes, and medicine bottles including a Paine’s Celery Compound bottle were found. Based on diagnostic artifacts, this deposit dates roughly around the turn of the 20th century. A brick stabilization wall divided the privy shaft in half from Levels 4-7, with a portion of a wood beam at the bottom. Ash deposits surrounding the wall and arch fall continue through Level 13. Moderate densities of artifacts including flower pots, lamp glass, rubber combs, flavoring extract bottles, metal, electrical wire, window glass, sewing machine oil, tin cans, celluloid, leather shoes, clay pipes, and a variety of ceramics, medicinal bottles, and butchered bone were found within the ash deposits. Temporally sensitive artifacts place this portion of the privy at mid 1890s. As the excavation progressed, it was noted that fragments from a single artifacts were found in several levels. For example, fragments from a badly shattered brown spongeware teapot were found in Levels 6, but also in Level 14 (8 feet further below). Excavations ceased at after Level 19 due to decreasing stability of the walls and cold temperatures. The southern half of the privy shaft was excavated (unscreened) to 24’6” and then a 5 foot soil core was used to determined if any changes in soil would occur. The same types of artifacts were encountered until the bottom 2” of soil, which contained a dark seed-bearing level (likely fecal matter). Cinadr and Genheimer note that it appears this privy was quickly filled around the turn of the 19th century. The privy shaft was likely not capped until after 1959, as mid-20th century artifacts including a 1959 dog tag were found in the upper levels.

An attempt to locate depositions related to the construction of the house was made with a 3’x6’ unit next to a wall of the original portion of the house. A small assemblage of a mix of 19th and 20th century artifacts were located in the first level, including portions of a Diet 7-up bottle near mid 19th century ceramic shards. The next level below included architectural artifacts, as well fragments from an aqua glass bottle embossed Dr. D. Jayne’s Oleaginous Hair Tonic, whose business began in 1839. A thin gray clay material was noted near the foundation of the house from Level 1 until Level 4, extending out from the house up to 13” and then retreating back to the 3” from the foundation in Level 4. A variety of construction material, early 19th century ceramics, and a fragment of prehistoric chert, along with a small chert projectile point were found in the horizon next to the clay material. The foundation was made of undressed limestone slabs, which stops short of extending to the basement floor. Based on the artifacts uncovered, Cinadr and Genheimer explain that it is likely that this building trench dates to the construction of the original house and was undisturbed after the first level.

The last portion of this story will focus on the analysis of the artifacts and the results from Cinadr and Genheimer’s excavation. Today the William Betts house, at 416 Clark Street, is open as a museum. Learn more about the Betts family history and their house check out The Betts House.

Dollars and Sense of Building Rehabilitation- Steubenville 4.11.14

Heritage Ohio is proud to announce another educational workshop to help individuals and communities understand the tools available for historic buildings. Our next Dollars and Sense Workshop will be held in Steubenville on April 11th. This workshop is located to be central to much of eastern Ohio. To view the agenda click Dollars and Sense of Building Rehabilitation

Ohio's List of 100

The Society of Architectural Historians has created an encyclopedia of important properties on their website, called the archipedia. A work in progress, the goal is to have each state’s 100 representative properties compiled by 2015. It is not hard to argue that Ohio has an amazing history, with a rich built environment. Barb Powers has been coordinating a representation of Ohio’s 100 most notable properties. The list is created from input, suggestions, and discussions with professionals in the field. The list is organized chronologically from the Serpent Mound in Adams County, to the Glass Pavilion in Toledo (2006), Ohio’s college campuses, and entries open for Presidential sites or Courthouse entries.

Now that the list has been created, the next step is creating descriptions for the entries. The first 10% of entries are due to SAH at the beginning of April. Those 10 selected have the most information and are those bolded in the list. Contact Barb Powers at bpowers@ohiohistory.org if you are interested in contributing a particular entry.

SAHArchipedia_OH_list_map 2014

Young Ohio Preservationists

Update 3/1/2016: The Young Ohio Preservationists have become a reality and are located at youngohiopreservationists.org!

One of my absolute favorite blogs is Preservation in Pink, so I found her post a few weeks back about young preservationists especially interesting. As you may be aware, Heritage Ohio has been active in working to help build a Young Ohio Preservationist movement, from developing a survey to get feedback about how 20-40 year old self-identified preservationists view themselves shaping preservation in Ohio, to holding one-on-one stakeholder interviews, to holding introductory planning meetings in Columbus this past January.

As the PiP author expresses in her blog post, preservationists in leadership positions have done a better job in recent years of actively engaging people under 40 to help shape the preservation movement. Although some bristle at the notion that a “Young Preservationist” appellation is even needed, preferring instead to seamlessly mesh with the rest of the preservation world, the concept of giving young preservationists special status within the preservation world has taken hold. A lot of Old Preservationists (myself included) are excited by the prospect of fresh ideas, and new ways of looking at (and saving) old buildings that young preservationists can bring to the table.

What do you think? Is there a place in the preservation world for groups of a specific age range?

![]()

Dollars and Sense of Rehabilitation

Heritage Ohio is again offering a series of workshops to help individuals and communities understand the historic building rehabilitation process.

We will be offering four workshops during 2014. Participants will have the opportunity to visit with representatives from Ohio Development Services Agency and the Ohio Historic Preservation Office. We will have a building owner share their experience in using historic tax credits, and other professionals involved in successful rehabilitation projects.

The next workshops will be:

February 24 in Dayton

April 11 in Steubenville

August 8 in Findlay

October 13 in Portsmouth

The Dollars and Sense of Building Rehabilitation- Athens August 12, 2013

For communities and building owners who want to know more about successful building rehabilitation.

First the community needs to set the stage, and create an environment where building rehabilitation is understood and encouraged.

Second, building owners need to understand how to deal with historic buildings and what tools are available to help.

Learn how you can be more successful at rehabilitating your historic buildings.

Register for this workshop HERE

A tale of two schools

As preservationists, we constantly fight the misconceptions and notions that people have about continuing to use existing buildings, or rehabbing buildings that have been vacant. I came across one such example a few weeks back in the Record Herald, Washington Court House’s daily newspaper.

The headline read “Jeffersonville school to be demolished soon” and the article briefly recounted the impending demise of a small-town school building. Quoted in the article, the county’s chief building official provided arguments about why the demolition, for a 1924 school building that had been vacant since 2008, was needed.

Demolition argument #1: the cost of retrofitting

“Usually those old buildings with the way they were built…we’re not able to retro-fit them with new mechanical things. The cost is just overwhelming.”

Demolition argument #2: since the building has been vacant for a period of time, demolition has inevitably become the only choice

“Sooner or later (old buildings) do become a hazard…It can’t go anywhere but down the longer it sits.”

What’s ironic is the last sentence of the article, discussing the site’s future once the school has come down:

Ideas being discussed for the future of that site include an apartment building and/or possibly a small park.

Now, let’s contrast the demise of the Jeffersonville School with the rebirth of the Hawthorne School in Dayton, a historic school building currently in use as, surprise, apartments!

Built in 1886 in McPherson Town, a picturesque Dayton neighborhood, the school served as an educational hub until 1974 when the district abandoned the building. The building served other purposes but was completely vacated in 1987, its age beginning to show. Although developers showed interest in the building, no viable proposal came forward until 1998 when the building was finally rehabilitated into residential apartments. In other words, the building sat vacant and in disrepair for 11 years before it was successfully redeveloped.

The redevelopment was a true public-private partnership as both the City of Dayton and the private developer brought their respective tools to the table: private equity, tax credit incentives, a city loan, HOME funds, and CDBG funds. The result still stands today: a historic apartment building that adds to the fabric of a historic neighborhood.

When comparing these two paths, what really stands out is the community mindset when making a decision about a vacant building. Does the community view the building as an asset to invest in, or does the community view the building as a liability. If these two schools switched communities, do you think the results would have been different: the Hawthorne building preserved in Jeffersonville, and the Jeffersonville school demolished in Dayton, because of the qualities of each building? Or is it the community mindset (and will to preserve) that ultimately signs a building’s death warrant, or grants its rebirth?

As our annual round of Top Preservation Opportunities comes up again this year, we hope to once again reach out to the “Jeffersonvilles” of Ohio and influence (and educate) the mindset of the historic, but vacant, building as a liability, to become a mindset of the building as asset. We’ll let you know what happens.

The Buck Starts Here: Fundraising for your organization!

We wanted to let you know that registration for “The Buck Starts Here” is now live. You can register here. What is “The Buck Starts Here” you ask? So glad you did! It’s a two-day training on February 25 & 26 that we’re very excited to bring to you, in partnership with the Ohio Historical Society, the Ohio Local History Alliance, and Goettler Associates. A training designed for small nonprofits, The Buck Starts Here will cover critical fundraising topics including:

Board Development (developing a board to take an active role in fundraising)

Case Statements (creating and fleshing out your organization’s case statement to assist you in making your case to funders)

Annual Campaigns (tips for running effective annual campaigns to provide your organization with a regular funding stream)

Donor Stewardship (learning how to develop meaningful relationships with your donor base to increase your funding base over time)

Effective fundraising is a critical skill for any small nonprofit to master. With this in mind we’ve kept the registration fee affordable at only $50 for the full two-day training, thanks to the generous support of the Jeffris Foundation. You’ll also have the option of joining us for dinner on Monday evening for $20 if you’d like. Each attendee will receive a notebook filled with information on fundraising for future reference.

We do require that two people from each organization register for the training in order to ensure each organization receives the most benefit from the training possible.

If you need accommodations while in Columbus, we’ve worked out a special room arrangement with The Westin Columbus for $109 per night. Just mention “Heritage Ohio” when making your reservation.

We hope you’ll plan to join us in Columbus, but hurry, space is limited, so register today!

Contact us at info@heritageohio.org or 614.258.6200 for more information and stay tuned to our website, eblasts, and Revitalize Ohio magazine for updates!

Round 9 Preservation Tax Credits…making and remaking history

Yesterday the Ohio Development Services Agency (the former Ohio Department of Development) announced the tax credit awards from the 9th Round of the Ohio Historic Preservation Tax Credit. You can read the full release here.

The big projects we’ve seen in the past are back again (Cleveland rehabs account for tens of millions of dollars in project costs); however, we also continue to see the emergence of smaller projects. The Lazarus House Apartments in Columbus will be rehabilitated into three apartment units in Columbus, at a total project cost of $265,860, taking a state tax credit of $46,195. While I love to see big projects such as the East Ohio Building in Cleveland with its 65 million dollar construction impact, I’m even more heartened to see the scale of projects receiving funding. I could envision the Lazarus Apartments happening in any of our Main Street communities, and I know if we can pump more construction investment into our Main Street communities, they will be better positioned to thrive far into the future.

Stay tuned to Heritage Ohio and Ohio DSA for updates on the state tax credit. For now, the next date to remember is March 30, 2013. Round 10 applications are due then.

Best wishes to you for a prosperous 2013 filled with preservation & revitalization!

Preservation Pop Quiz…where is this courthouse?

Heritage Ohio’s Preservation Pop Quiz is back (thanks to Preservation in Pink for supplying a great blog idea!) One of my favorite buildings in Ohio is pictured below. It’s a county courthouse that looks much like it did when it was constructed in 1858.

Here’s an additional visual hint: the courthouse features nearly symmetrical wings. The north wing pictured below originally housed the Recorder’s and Treasurer’s offices. Can you guess the city and county where this iconic historic courthouse is located?

Submit your answers in the comments section below. We’ll update you soon with the answer to the location question. Good luck!

Answer Update: The above images show the Ross County Courthouse in historic downtown Chillicothe. Happy Thanksgiving everyone!